Exploring New Approaches to Math Instruction

Throughout this numeracy course, I was introduced to a wide range of resources, tools, and strategies that challenged how I had previously thought about math instruction. I began to consider how math could be taught in ways that are more interactive and engaging for students of all ages. Thes approaches emphasized the importance of student thinking, visuals, and manipulatives, as a part of everyday math instruction, not just formal lessons.

Montessori Math: Visual and Tactile Thinking

One of the key learning moments for me was exploring Montessori-style math materials with Jody Hoffman, especially the beaded chains and stamp games. These materials give students a concrete, visual way to understand number sequencing, skip counting, and place value. Being able to physically manipulate the beads supports students in developing a deeper number sense, especially in early grades.

It also made me reflect on my own math learning. While I did use manipulatives in the primary years, they were not commonly used as I progressed into the intermediate grades. I now see how beneficial it would have been to continue using tools like these to explore multiplication, division, and fractions more deeply. I also appreciate that materials like the beaded chains are adaptable, not just for primary students, but for older grades as well. They can be used to revisit concepts in ways that support different types of learners.

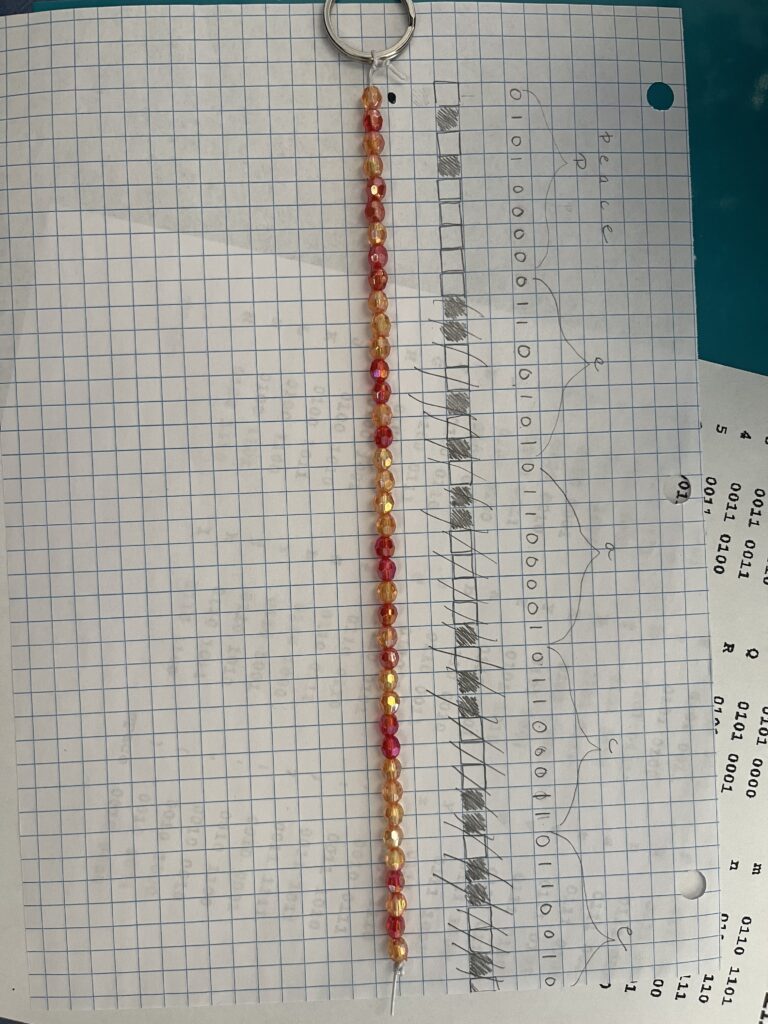

Beaded Tweets with Noelle Pepin

Noelle Pepin was generous enough to visit our class via zoom and share her project called Beaded Tweets, which was developed as part of her master’s degree. This framework combines coding with beading, using messaging platforms like Twitter as inspiration. Each letter or number is represented by a specific eight-bead pattern, and students select two colours to code their chosen message or phrase.

I really appreciated the way Noelle emphasized the importance of setting intentions before beginning the beading process. The act of beading becomes a mindful and creative practice, where students are engaged both artistically and intellectually. This was such an interesting way to introduce students to coding, especially because it does not rely solely on technology. It gives students an opportunity to explore patterning, coding, and meaning-making using their hands and imagination.

It’s also a great example of interdisciplinary learning as it is connecting math with art, culture, and language. Noelle clearly outlined how Beaded Tweets aligns with the First Peoples Principles of Learning. In particular, she explained how the thread can represent the journey of past, present, and future, which ties directly into Indigenous pedagogy. I could see this being a valuable and meaningful classroom activity, especially as a quiet task for early finishers or as part of a longer inquiry unit.

High Yield Routines and Daily Math Discussions

We also explored several high yield math routines with Jennifer Dionne. These included short, structured activities like Number Talks, Which One Doesn’t Belong, Esti-Mysteries, and Open Questions from Steve Wyborney. These routines are designed to be quick but effective ways to build number sense and reasoning skills without needing a full lesson.

One aspect I found helpful was the focus on creating a low-stakes environment for students to share their thinking. In particular, Number Talks encouraged multiple ways of noticing and problem-solving. A simple question like “How many paper clips do you see?” can lead to a rich discussion about counting strategies, grouping, and estimation. These routines give students space to explore math without the pressure of getting the “right” answer immediately.

Another element I appreciated was the use of sign language cues to support inclusive participation. Students can use gestures like a closed fist to signal they are thinking, one or two fingers to show how many strategies they’ve come up with, and the “me too” wave to indicate agreement. These small, non-verbal strategies help build classroom community and give all learners a voice.

The Purposeful Use of Math Games

Another takeaway from this course was the importance of intentionality when using math games. We learned that games should not just be used for fun, they need to support meaningful learning. That means making sure students have been taught the strategy before the game is introduced and being clear about the learning goals connected to the activity.

When used intentionally, math games can help reinforce fluency, encourage strategic thinking, and provide a collaborative environment for students to learn from one another.

Final Reflection

This course helped me reframe what it means to teach math in for all ages. I now understand the importance of building routines that promote discussion, using manipulatives that support understanding, and making space for creativity and hands-on exploration. The biggest shift for me is recognizing that math instruction can (and should) look different depending on the needs of the learners, and that it does not have to be worksheet-based or fast-paced to be meaningful.

I feel more confident in my ability to facilitate math learning that is intentional, inclusive, and engaging. This course has provided me with a solid foundation of strategies and resources that I will carry with me into my future classroom.

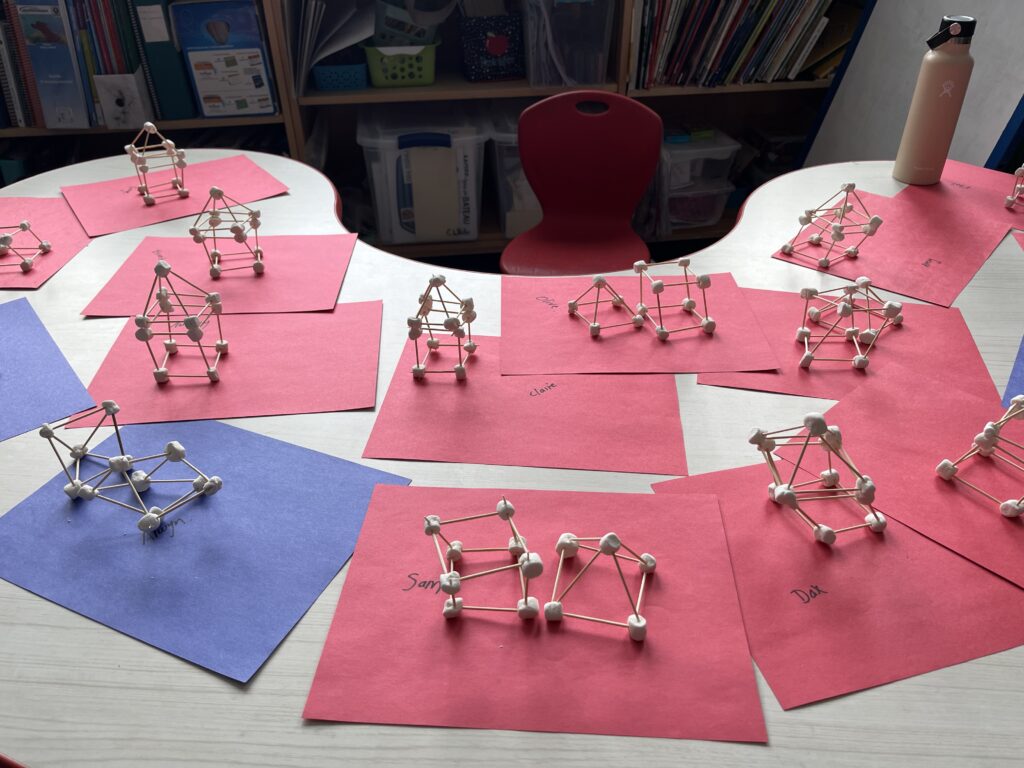

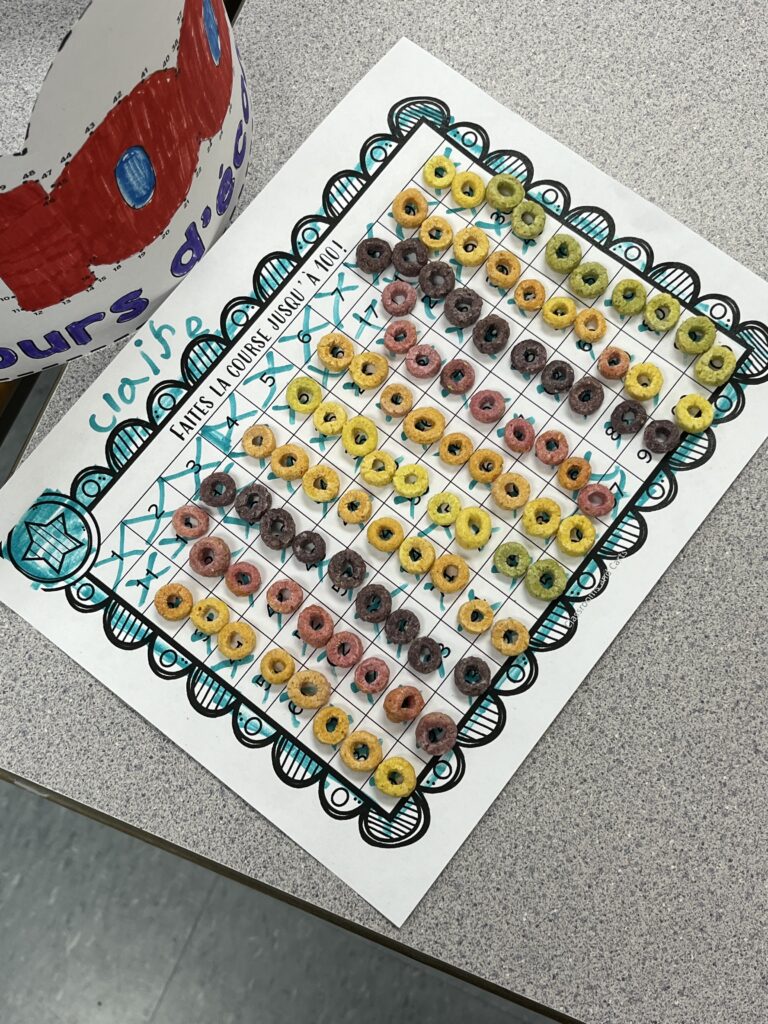

Math activities I facilitated during my practicum in a K/1 FRIMM class!