My name is Shyla Hampole, and I was born and raised in Prince George, a city situated on the unceded ancestral lands of the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation. In the Dakelh (Carrier) language, Lheidli T’enneh translates to “the People from the Confluence of the River.” These symbolic words reflect the geography of the territory, as the Nechako River flows north from the Nechako Plateau, then turns east toward Prince George, where it joins the Fraser River to form a single channel.

Just beyond the downtown area of Prince George is a park once known as Fort George Park. It is filled with gardens and diverse tree species, offering a pristine view of the Fraser River. Many of my happiest childhood memories were made in this park, having picnics, playing in the water park with my younger brother, and drinking copious amounts of iced tea. At the centre of the park lies a small cemetery, which I often pondered as a child. I wondered why it was in such a public space, unfenced, and seemingly unprotected. These thoughts quickly faded as I was drawn back to play and the calls from my family for lunch.

Throughout the seasons, I always found myself returning to the park. It became a place of comfort and solace. It was a space where I could gather with friends and be lively, or a place of solitude where I could sit quietly on a bench, reflecting as I watched the river’s currents flow. It wasn’t until my later teenage years that I learned the deeper historical, spiritual, and cultural significance of the park, the rivers, and the territory of the Lheidli T’enneh. During this time, I also became more aware of my own settler-colonial presence.

Growing up in a northern, somewhat secluded, and relatively conservative-minded region of British Columbia, my exposure to Aboriginal and Indigenous history was limited. Although I learned about Aboriginal and Indigenous history in school, there was a persistent disconnect between the curriculum and the reality of how Indigenous peoples were treated in the community. We were taught about the residential school system, but I didn’t fully grasp how the homelessness and poverty affecting Indigenous people in the community were direct outcomes of Canada’s policies of forced assimilation and cultural genocide. The narratives I often heard from peers and their families tended to shift the blame onto Indigenous communities. Their rhetoric often failed to recognize the systemic roots of these challenges. It was only later in my early adulthood that I came to understand that these views were shaped by ignorance and deeply ingrained biases.

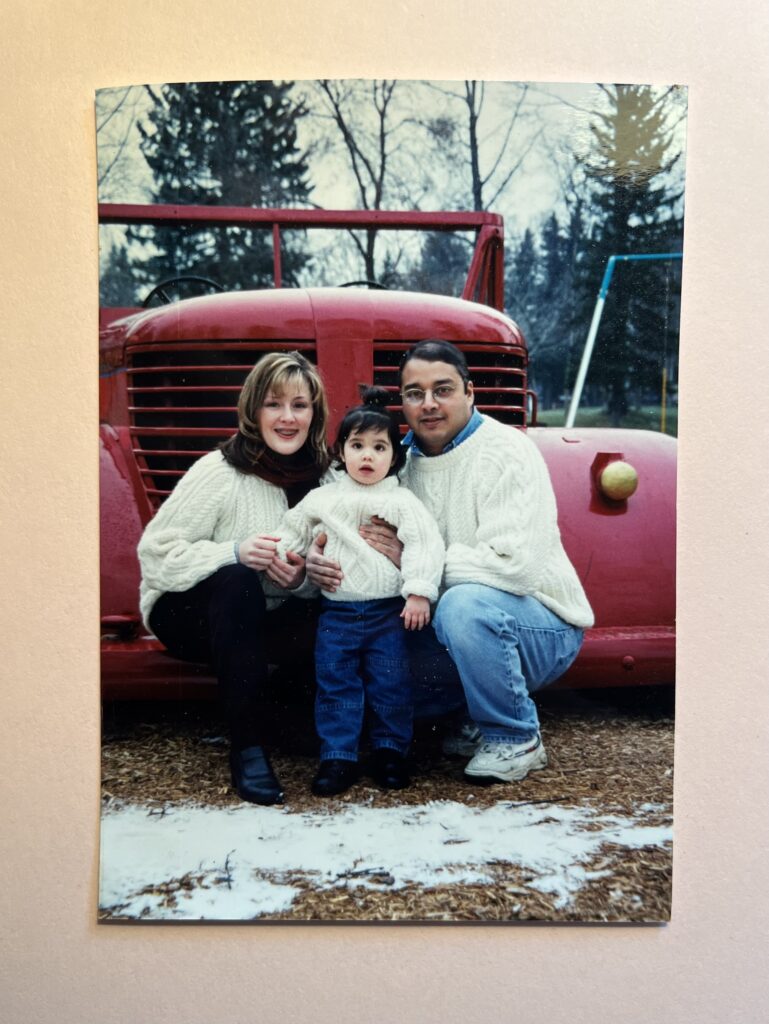

As a child of mixed heritage, my mother is of Irish and English descent from Newfoundland, and my father is South Indian, born to parents who immigrated from India to Saskatchewan in the 1950s, I also struggled with my identity. Growing up, classmates frequently questioned my ethnicity. They often guessed incorrectly and sometimes even asked if I was adopted. Constant comments about my racial ambiguity, while not overtly harmful, deepened my struggle to embrace my heritage. These experiences, though minor compared to the violent discrimination many ethnic minorities face, became part of my own process of self-awareness within Prince George.

To better understand my ethnic heritage and my complex relationship with Prince George, a city that brought me both joy and frustration, I decided to move to Victoria and attend the University of Victoria as an undergraduate student. My goal was to deepen my knowledge of Aboriginal and Indigenous ways of knowing. While pursuing my English undergraduate degree, I made it a priority to enroll in courses about Canada’s true history as well as courses involving Aboriginal and Indigenous voices and cultural diversity. My hope was that by gaining a more comprehensive understanding, I could return to Prince George with a new perspective and work towards fostering greater awareness and reconciliation in my community.

Last year, I returned to Prince George and began teaching in School District No. 57 as an uncertified educator. As a first-time teacher, I was understandably nervous and apprehensive due to my own experiences within the school system. However, these fears quickly dissipated when I was warmly welcomed at the first school I worked at. I was impressed by how the curriculum had evolved to emphasize inclusivity and a celebration of diversity. I was particularly pleased to see the First Peoples Principles of Learning as foundational components of the new curriculum. Overall, I felt a profound shift from the Prince George I had previously known and left behind. I felt a sense of pride and excitement for this new generation of students as they will hopefully become more informed, empathetic, and engaged citizens.

While there is still significant work to be done regarding reconciliation, I am starting to see the Prince George community become more inclusive and honest about its violent and discriminatory past. Sadly, where inclusion and hope exist, ignorance and hatred can also persist. Nevertheless, I believe that through honest and inclusive education, hope and authenticity will ultimately prevail.

During my orientation for the Bachelor of Education Program at the University of Northern British Columbia, I returned to what is now the Lheidli T’enneh Memorial Park for the first time since leaving Prince George. I was quickly overwhelmed by the memories of my childhood spent in the park and reflected on how my connection to and respect for the land and the rivers has deepened over time. Through the stories I have learned and will hopefully continue to learn as a future educator and active member within the Prince George community, I hope to honour the Lheidli T’enneh through my appreciation of the land and its enduring cultural heritage.